For years, Medicare couldn’t negotiate drug prices. That meant billions in spending went straight to pharmaceutical companies with no leverage to bring costs down. But everything changed in 2022 when the Inflation Reduction Act gave Medicare the power to directly negotiate prices for the most expensive single-source drugs. Starting January 1, 2026, this new system kicks in - and it’s already cutting prices by up to 79% for some of the most commonly used medications.

What’s Actually Changing?

Before this law, Medicare Part D - the prescription drug plan for seniors - had to accept whatever price drugmakers set. Private insurers could negotiate rebates behind the scenes, but Medicare was locked out. That left beneficiaries paying high list prices, even when insurers got discounts. Now, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) can step in and say: ‘This drug costs too much. We’re paying X.’

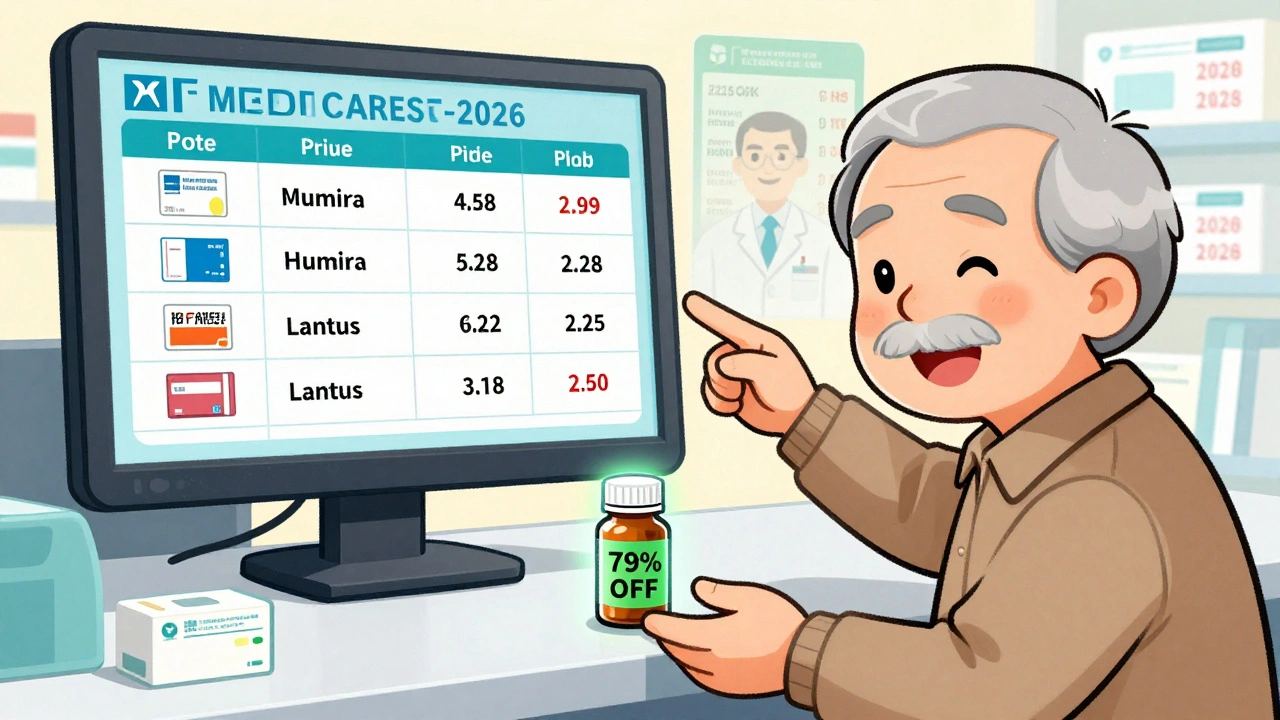

The first 10 drugs selected for negotiation include big-name medications like Eliquis (for blood clots), Jardiance (for diabetes), and Xarelto (another blood thinner). These aren’t cheap generics. They’re brand-name drugs with no competitors, and they’re used by millions. In 2022, just these 10 drugs cost Medicare $50.5 billion. Now, CMS has locked in discounts ranging from 38% to 79% off previous prices.

For example, Eliquis - which cost $500 per month for many patients - will now be priced at around $300 or less under the new deal. That’s not a small change. It’s life-altering for someone on a fixed income.

How the Negotiation Process Actually Works

This isn’t a backroom deal. It’s a legal, step-by-step process with strict deadlines and public records.

- On February 1, 2024, CMS sent each drugmaker an initial offer - backed by data on how much the drug costs elsewhere, how many people use it, and what alternatives exist.

- Drugmakers had 30 days to respond with a counteroffer.

- CMS then held three formal negotiation meetings with each company between March and July 2024.

- By August 1, 2024, all negotiations were closed. Five drugs agreed during meetings; the other five were finalized through written offers.

- Final prices were published on August 16, 2024, and will take effect January 1, 2026.

The rules are clear: the final price can’t be higher than two benchmarks - either the average net price insurers paid last year, or a percentage of the drug’s national average price. CMS didn’t guess. They used real data. And they didn’t back down.

Why This Matters for You

If you’re on Medicare Part D, you’ll see lower out-of-pocket costs starting in 2026. But it’s not just about the sticker price. The new system changes how you get care.

Before, insurers could push you toward cheaper drugs - even if your doctor recommended something else. Now, with lower prices across the board, you’re more likely to get the medication your doctor prescribes without hitting a coverage barrier. That’s huge for people with chronic conditions like heart disease, diabetes, or arthritis.

Also, the law caps your annual out-of-pocket drug spending at $2,000 starting in 2025. Combine that with lower drug prices, and your total cost drops even more. For someone taking multiple high-cost meds, that could mean saving over $1,000 a year.

What About Private Insurance?

You might wonder: ‘Does this affect me if I’m not on Medicare?’

Yes. Private insurers often use Medicare’s pricing as a reference point. When Medicare negotiates a lower price, insurers start asking for similar discounts. This is called the ‘spillover effect.’

One analysis estimated that private insurers could save $200-250 billion over the next decade just by following Medicare’s lead. That means lower premiums, lower copays, and fewer surprise bills for people with employer-sponsored plans too.

Some companies have already started adjusting. CVS Health and UnitedHealthcare have said they’ll align their pricing with Medicare’s new rates. It’s not a requirement - but it’s smart business. Why pay more when Medicare’s paying less?

What Drugs Are Next?

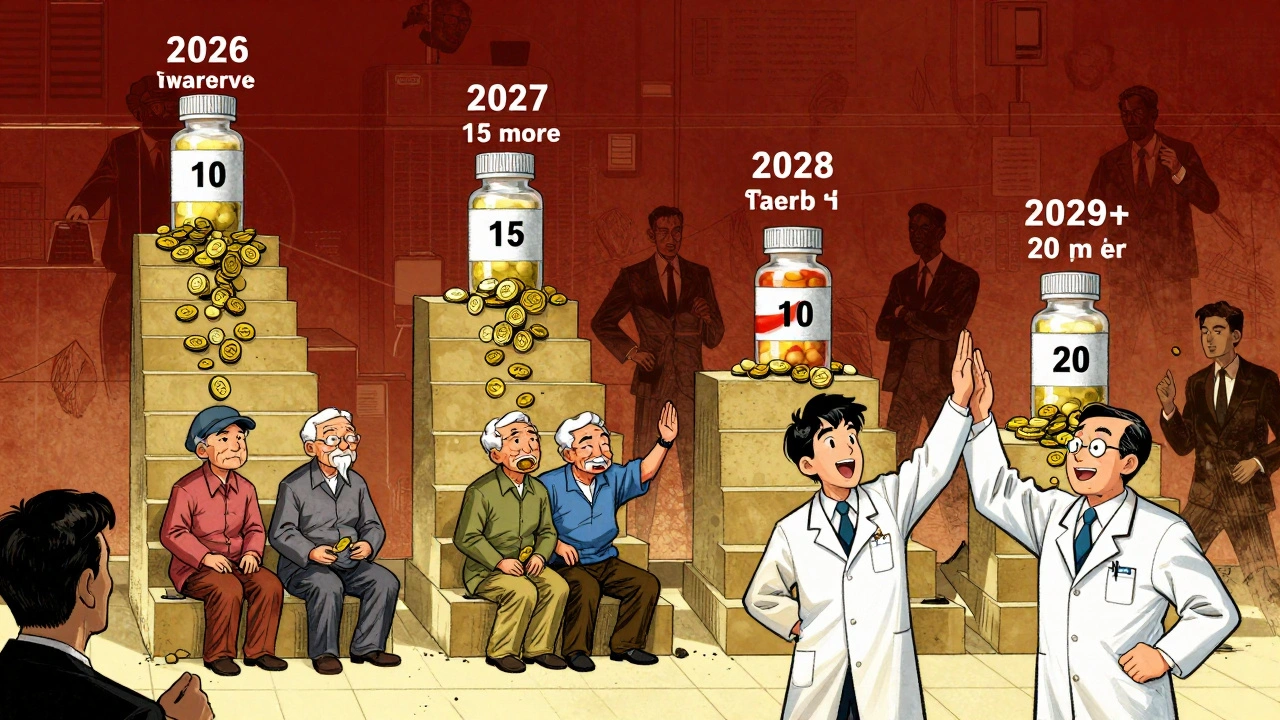

This isn’t a one-time fix. The law is designed to scale up.

- 2026: 10 drugs

- 2027: 15 more

- 2028: 15 more - including drugs given in doctor’s offices (Part B)

- 2029 and beyond: 20 drugs per year

The next batch includes drugs like Farxiga (for diabetes and heart failure) and Stelara (for psoriasis and Crohn’s disease). These are expensive, long-term treatments. Negotiating them will save billions more.

But here’s the catch: only drugs that are at least 7 years old (or 11 years for biologics) are eligible. That means brand-new miracle drugs - like the latest cancer treatments - are protected from negotiation for now. Critics say that’s too long. Supporters say it gives companies time to recoup R&D costs.

Who’s Fighting This - and Why?

Four drugmakers sued to stop the program, claiming it was unconstitutional. Their argument? The government can’t force them to sell at a lower price.

On August 2, 2024, a federal judge dismissed all four lawsuits. The ruling said Congress had the right to set this rule. Appeals are expected, but for now, the program moves forward.

Drug companies also argue this will hurt innovation. They claim they’ll lose $112 billion in revenue over 10 years and won’t be able to develop new drugs.

But the White House’s own analysis says those numbers are exaggerated. The Office of Management and Budget found PhRMA’s estimates were ‘significantly overstated.’ In fact, drugmakers still make money - just less. Eliquis maker Bristol Myers Squibb still expects to earn billions from the drug, even at the new price.

What This Means for Doctors and Pharmacies

It’s not just patients who feel the shift. Doctors and pharmacies have to adapt too.

For Part B drugs - things like injections given in clinics - reimbursement changes from ‘Average Sales Price + 6%’ to ‘Negotiated Price + 6%.’ That means clinics will earn less per dose. Some small practices worry they’ll lose money on these drugs and may stop offering them.

Pharmacies are updating their systems. By October 15, 2025, all Part D pharmacies must have the new prices loaded into their software. If they don’t, patients could be overcharged.

Training has already started. Over 78% of pharmacy benefit managers have launched staff training programs just for this rollout.

What You Should Do Now

You don’t need to do anything yet. The changes start in 2026. But here’s what you can do now:

- Know your drugs. Check if you’re taking any of the first 10 negotiated drugs. Look up your medication on Medicare’s website.

- Compare plans. In 2025, during Open Enrollment, look for plans that already reflect lower drug costs. Some may advertise ‘Medicare Negotiated Pricing’ as a perk.

- Ask your pharmacist. When you refill a prescription, ask: ‘Is this price going down in 2026?’ They’ll know.

- Don’t switch drugs unnecessarily. Your doctor prescribed a specific medication for a reason. Don’t trade it for a cheaper one unless your provider agrees.

By 2027, you’ll have even more options. And by 2028, when Part B drugs are included, people getting infusions or injections will see big savings too.

Is This the End of High Drug Prices?

No. But it’s the biggest shift in decades.

The U.S. still pays more for drugs than any other country. Canada, the UK, and Australia use government price controls. This program doesn’t go that far - but it’s a start. It proves Medicare can negotiate. And once it does, it won’t stop.

Next up: biosimilars. These are cheaper versions of biologic drugs. Right now, uptake is low - under 30% even after 18 months. But as Medicare pushes for lower prices, insurers will push harder for biosimilars. That’s the next wave of savings.

And the FTC is cracking down on ‘product hopping’ - when companies tweak a drug slightly just to delay generics. That’s another way prices stay high. If that stops, more drugs will become eligible for negotiation sooner.

This isn’t perfect. But it’s real. And it’s working.

Which drugs are included in the first round of Medicare price negotiations?

The first 10 drugs selected for Medicare negotiation in 2026 include Eliquis (apixaban), Jardiance (empagliflozin), Xarelto (rivaroxaban), Farxiga (dapagliflozin), Invokana (canagliflozin), Linagliptin, Januvia (sitagliptin), Enbrel (etanercept), Humira (adalimumab), and Lantus (insulin glargine). These were chosen because they’re high-cost, single-source drugs with no generic or biosimilar competition and are used by large numbers of Medicare beneficiaries.

How much will my prescription costs go down?

It depends on the drug. Negotiated discounts range from 38% to 79%. For example, Eliquis, which cost about $500 a month, will drop to roughly $300 or less. For people taking multiple high-cost drugs, total annual savings could be $1,000 or more. The 2025 out-of-pocket cap of $2,000 also helps - so even if your drug isn’t negotiated yet, your total spending is capped.

Will this affect my private insurance?

Yes, indirectly. Private insurers often use Medicare’s negotiated prices as a benchmark. Many are already lowering their rates to match. Analysts estimate private plans could save $200-250 billion over 10 years, which may lead to lower premiums and copays for people with employer-based or individual insurance.

Why are only older drugs being negotiated?

The law requires drugs to be at least 7 years old (or 11 years for biologics) to qualify. This was designed to protect innovation - giving companies time to recoup research costs before facing price talks. Critics argue this delays savings, but supporters say it balances affordability with incentives for new drug development.

What happens if a drugmaker refuses to negotiate?

They don’t get a choice. If a company doesn’t respond or refuses to agree, CMS sets the price anyway - based on the statutory formula. The company then faces a tax penalty equal to 95% of the difference between their last offer and CMS’s final price. That’s a strong incentive to come to the table.

Will I be forced to switch to a different drug?

No. Your doctor still chooses your medication. The goal of negotiation is to lower prices so you can keep your current drug without financial hardship. In fact, lower prices may make it easier for you to get the drug your doctor recommends, rather than being pushed toward a cheaper alternative.

When will Part B drugs be included?

Part B drugs - like injections given in clinics - will be included starting in 2028. The first batch of 15 Part B drugs will be announced in 2025, with negotiations completed by November 2025. This will affect drugs used for cancer, autoimmune diseases, and other chronic conditions administered by providers.

Is this program legal?

Yes. Four drug companies sued to stop the program, claiming it violated constitutional rights. In August 2024, a federal judge dismissed all lawsuits, ruling that Congress had the authority to set this pricing rule. Appeals are expected, but the program is moving forward as planned.

Finally. I’ve been paying $400 a month for Eliquis since 2020. My pension doesn’t stretch that far. This isn’t a handout-it’s justice. I’m not mad, I’m just tired of being robbed by companies who think we’re dumb enough to keep paying.

Thank you, Congress. Even if it took forever.