Ibuprofen Environmental Impact Calculator

How Your Ibuprofen Use Impacts Waterways

Estimate how much ibuprofen from your personal use enters rivers and lakes based on consumption and disposal habits

Your estimate will appear here

When you pop a pill for a headache, you probably don’t think about where it goes after you’re done. Ibuprofen is one of the world’s most used pain relievers, and a surprising amount of it ends up in rivers, lakes, and even drinking water. This article walks through how ibuprofen gets into our waterways, what it does to the ecosystem, and what we, scientists, and policymakers can do to curb the damage.

Key Takeaways

- Ibuprofen is detected in surface water worldwide at concentrations ranging from a few nanograms to several micrograms per liter.

- Conventional wastewater treatment plants only remove 20‑80% of ibuprofen, leaving a measurable residue.

- Even low‑level exposure can disrupt fish reproduction, alter algae growth, and promote antimicrobial resistance.

- Advanced treatment options like activated carbon and membrane filtration dramatically improve removal rates.

- Regulatory frameworks are catching up, but public awareness and proper disposal remain critical.

What is Ibuprofen and How It Enters the Water Cycle

Ibuprofen is a non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drug (NSAID) that reduces pain, fever, and inflammation. It works by blocking the cyclooxygenase enzymes COX‑1 and COX‑2, which produce prostaglandins that signal pain and swelling. In 2024, global sales topped 30 000 tons, making it one of the top‑selling pharmaceuticals. Most of the drug is taken orally, metabolized partially, and excreted unchanged in urine and feces. Because human metabolism only breaks down about 50‑70% of the dose, the rest travels straight to sewage systems.

Household waste disposal is the biggest pathway: flushing unused pills, rinsing medicine containers, or pouring leftovers down the sink. Once in the sewage network, ibuprofen joins a cocktail of pharmaceutical residues that include antibiotics, hormones, and antidepressants. These compounds are collectively called pharmaceuticals in environmental discussions.

How Much Ibuprofen Is Really in Our Water?

Monitoring programs in Europe, North America, and Asia have quantified ibuprofen levels in rivers and lakes. Below is a snapshot of reported concentrations from 2022‑2024 studies.

| Region | Average | Maximum reported |

|---|---|---|

| Western Europe | 0.05 | 0.27 |

| North America | 0.03 | 0.19 |

| East Asia | 0.08 | 0.42 |

| Australia/New Zealand | 0.02 | 0.11 |

Even at the low end, these numbers are far above the predicted no‑effect concentration (PNEC) for many aquatic species, which sits around 0.01 µg/L.

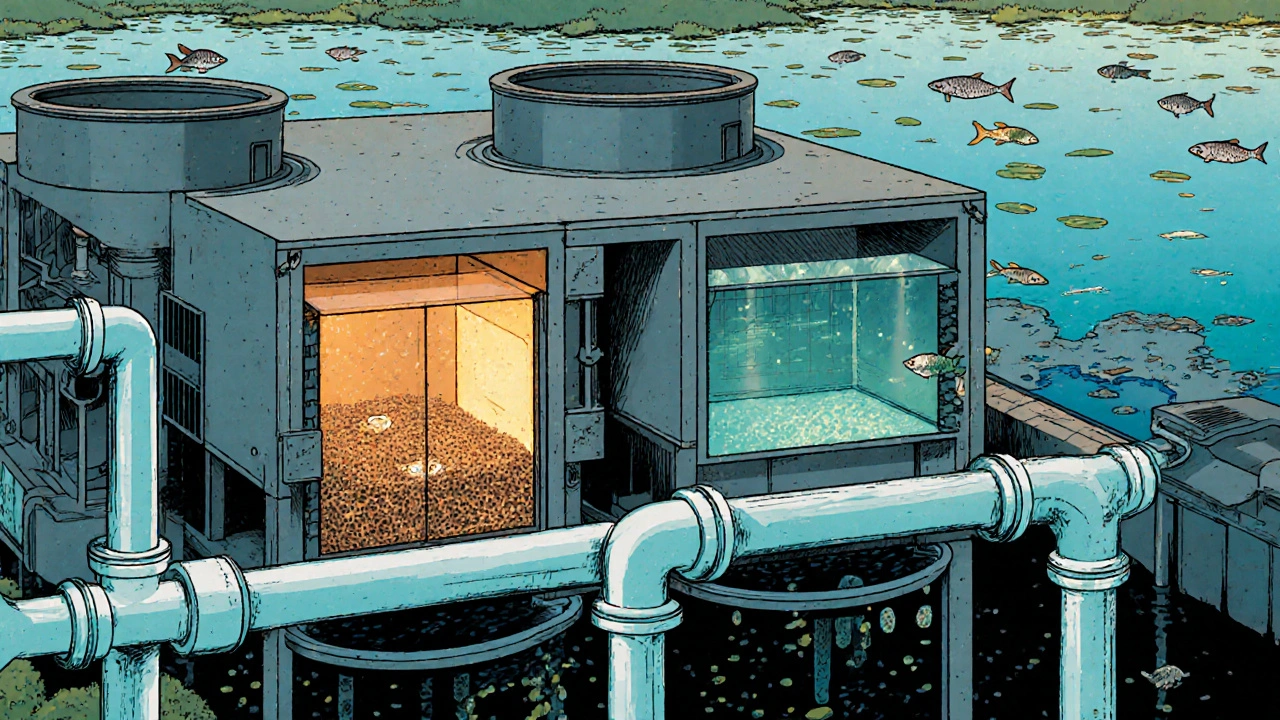

Why Conventional Wastewater Treatment Struggles

Most municipal plants rely on primary sedimentation, biological aerobic digestion, and secondary clarification. While these steps are great for organic matter and nutrients, they’re less effective against polar, low‑molecular‑weight compounds like ibuprofen.

Studies show removal efficiencies ranging from 20 % in older plants to about 80 % in newer facilities that add tertiary polishing steps. The main mechanisms are adsorption to sludge and limited biodegradation. The fraction that slips through ends up in the effluent discharged to rivers.

Wastewater treatment plant upgrades can dramatically improve outcomes. Below is a comparison of common advanced treatment technologies for ibuprofen removal.

| Technology | Typical removal % | Key advantage | Implementation cost (USD/kW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activated carbon adsorption | 85‑95 | High affinity for polar molecules | 150‑250 |

| Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) | 90‑99 | Breaks down molecules into harmless fragments | 300‑450 |

| Membrane filtration (NF/RO) | 95‑99 | Physical barrier, no chemicals | 400‑600 |

| Constructed wetlands | 30‑60 | Low energy, natural habitat | 50‑100 |

Implementing AOPs or membrane filtration can push removal above 95 %, but the financial and energy demands are still a barrier for many municipalities.

Ecological Consequences: From Fish to Algae

Research on aquatic organisms shows that ibuprofen interferes with prostaglandin pathways that are essential for reproduction and stress response.

- Fish reproduction: Exposures as low as 0.1 µg/L reduce egg production in zebrafish and cause developmental abnormalities in medaka.

- Algal growth: Low‑dose ibuprofen can act as a hormone‑like cue, altering photosynthetic efficiency and leading to harmful algal blooms.

- Microbial communities: Chronic presence of ibuprofen promotes antimicrobial resistance by selecting for bacteria that carry multi‑drug resistance plasmids.

These sub‑lethal effects cascade up the food web. Predatory fish accumulate ibuprofen indirectly through their diet, a process known as bioaccumulation. While the chemical itself doesn’t reach the high concentrations needed for acute toxicity, its long‑term endocrine disruption is a growing concern.

Human Health Angles: Is Our Drinking Water at Risk?

Most drinking water utilities apply additional polishing steps-often chlorination and filtration-before distribution. Residual ibuprofen levels in finished tap water are typically below 0.01 µg/L, far under most health‑based guidelines. However, vulnerable populations (e.g., infants and pregnant women) may be more sensitive to endocrine‑disrupting compounds.

Long‑term epidemiological data are scarce, but animal studies suggest that chronic low‑dose exposure could affect kidney function and alter gut microbiota composition. The precautionary principle advises minimizing unnecessary exposure, especially for children.

Mitigation Strategies: From Individuals to Policy

Everyone can play a part:

- Proper disposal: Use take‑back programs, pharmacy drop‑boxes, or hazardous‑waste facilities instead of flushing.

- Right‑size prescribing: Doctors can prescribe the smallest effective dose and limit repeat prescriptions when possible.

- Green pharmacy research: Developing ibuprofen analogs that break down quickly in sewage.

At the institutional level, many European nations have adopted the European Union Water Framework Directive, which sets “watch‑list” status for pharmaceuticals, triggering monitoring and risk assessment.

In the United States, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency released a 2023 “Pharmaceuticals in Water” strategic plan, encouraging utilities to pilot advanced treatment and to share data through the National Water Quality Monitoring Council.

Other regions, like Australia and New Zealand, are piloting stormwater capture systems that filter out pharmaceuticals before they reach rivers.

Monitoring and Future Outlook

Continued surveillance is essential. Emerging tools like high‑resolution mass spectrometry enable detection of ibuprofen at sub‑nanogram levels, while passive samplers provide cost‑effective, long‑term data.

Looking ahead, a combination of tighter prescription guidelines, upgraded treatment infrastructure, and public education could cut ibuprofen loads to waterways by up to 70 % within the next decade.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does ibuprofen end up in rivers?

Most ibuprofen is excreted unchanged after you take it. When you flush unused pills or wash them down the sink, the drug travels through the sewage system and, because conventional treatment removes only a fraction, it is discharged with the treated effluent.

Are there safe levels of ibuprofen in drinking water?

Current guidelines consider levels below 0.01 µg/L to be of low risk for human health. Most municipal supplies meet this threshold, but ongoing monitoring is recommended, especially for vulnerable groups.

What treatment methods remove ibuprofen most effectively?

Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), activated carbon adsorption, and membrane filtration (nanofiltration/reverse osmosis) consistently achieve >90 % removal, outpacing conventional biological treatment.

Can ibuprofen affect fish populations?

Yes. Even nanogram‑per‑liter concentrations can disrupt fish hormone systems, reducing spawning success and causing developmental defects in offspring.

How can I dispose of leftover ibuprofen safely?

Use pharmacy take‑back programs, community hazardous‑waste collection events, or follow local government guidelines. Never flush pills or pour them down the drain.

I had no idea ibuprofen ends up in rivers.