Absolute vs Relative Risk Calculator

Understand the real impact of medical treatments by seeing both absolute and relative risk differences. Enter your baseline risk and the risk after treatment to see what these numbers actually mean.

Your Baseline Risk

Risk After Treatment

Absolute Risk Difference

Absolute Risk Reduction

Relative Risk Impact

Relative Risk Reduction

Number Needed to Treat

Number Needed to Treat (NNT)

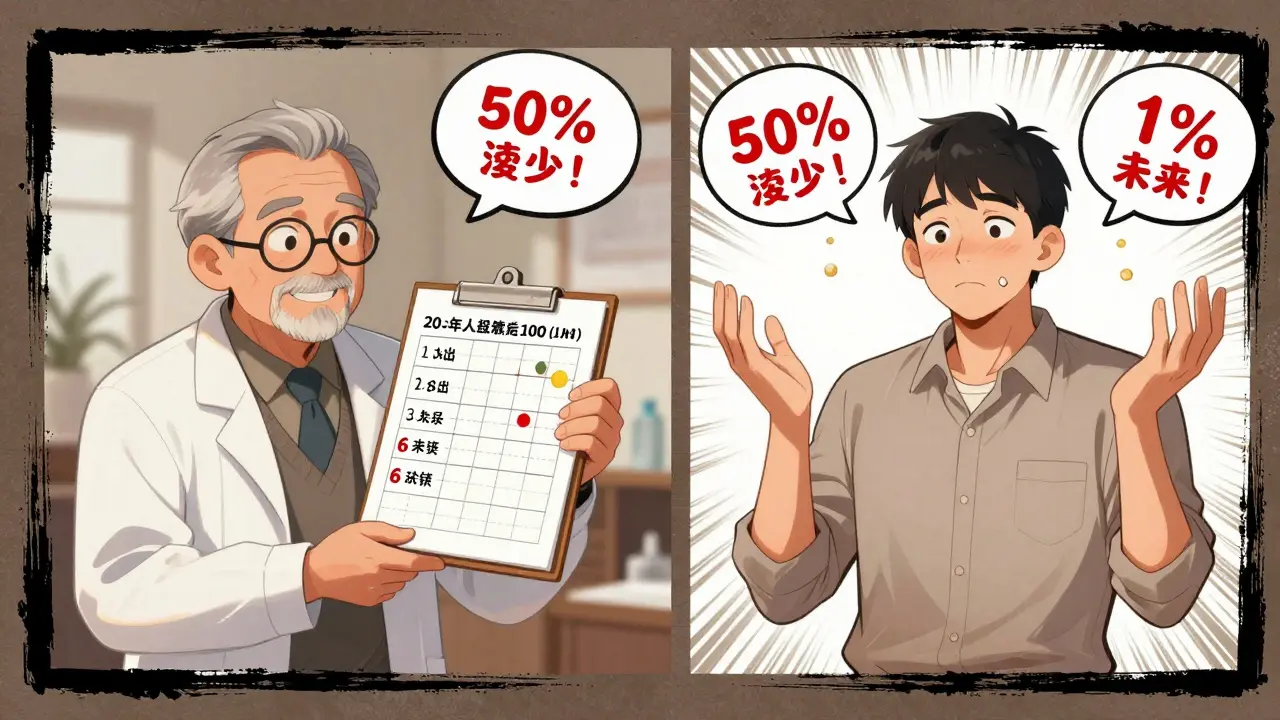

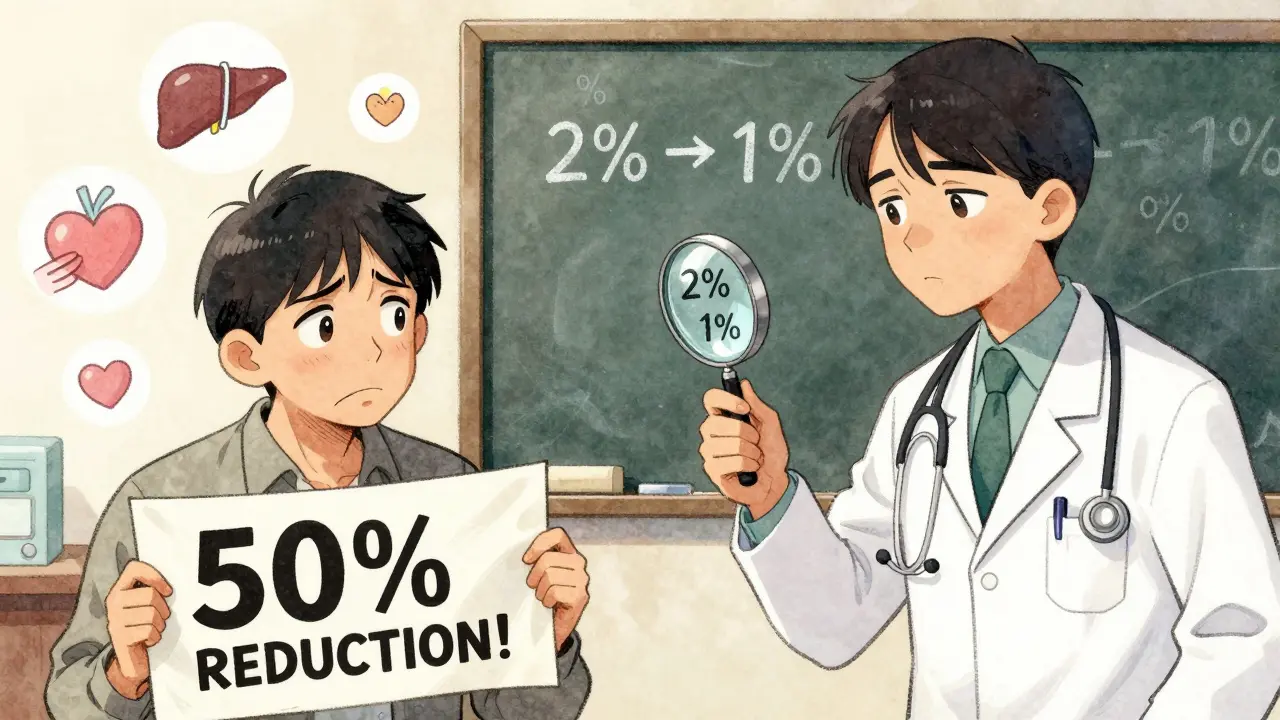

When a drug ad says it "cuts your risk of heart attack in half," you might think you’re avoiding a 50% chance of having one. But what if your actual risk was only 2% to begin with? After taking the drug, it drops to 1%. That’s not a 50% chance avoided - it’s a 1 percentage point improvement. This gap between what you hear and what’s true is the difference between absolute risk and relative risk. And it’s one of the most common ways drug companies make side effects and benefits sound bigger than they are.

What Absolute Risk Really Means

Absolute risk is the actual chance something will happen to you. It’s not a comparison. It’s just you, your body, and the numbers. If 1 in 10,000 people who take a certain drug get a rare liver problem, that’s an absolute risk of 0.01%. If 1 in 100 people get a headache, that’s 1%. These numbers tell you exactly how likely something is to happen - no math tricks, no spin.Doctors use absolute risk to decide if a treatment’s benefit outweighs its danger. For example, if a drug reduces stroke risk from 4% to 3% in someone with high blood pressure, the absolute risk reduction is just 1%. That means 100 people need to take the drug for one person to avoid a stroke. That’s called the Number Needed to Treat (NNT), and it’s calculated by dividing 1 by the absolute risk reduction (1 ÷ 0.01 = 100). If the side effects are serious - like muscle pain, kidney stress, or bleeding - that 1% gain might not be worth it for many people.

Here’s another example: A cholesterol drug might reduce heart attack risk from 5% to 4% over 10 years. That’s a 1 percentage point drop. Sounds small? It is. But if you’re 65, have diabetes, and smoke, your baseline risk might be 15%. Then a 1% drop means you’re going from 15% to 14% - still a big deal. Absolute risk depends on your personal situation. That’s why it matters more than any percentage you hear on TV.

What Relative Risk Makes You Believe

Relative risk compares two groups: people who took the drug versus those who didn’t. It’s a ratio. If the drug cuts your risk from 2% to 1%, the relative risk reduction is 50%. That’s because 1% is half of 2%. It sounds impressive. And that’s the point.Pharmaceutical ads love relative risk because it makes tiny benefits look huge. A drug that reduces cancer risk from 0.01% to 0.005% has a 50% relative risk reduction. That sounds like a miracle. But in absolute terms, you’re going from 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 20,000. That’s a 0.005% improvement. For most people, that’s meaningless. But if you’re in a high-risk group - say, you have a BRCA gene mutation - then that same drug might drop your risk from 70% to 35%. Now the 50% relative reduction means something real.

The problem isn’t that relative risk is wrong. It’s that it’s often shown alone. When an ad says, "This drug reduces heart attack risk by 50%," they’re not telling you your starting risk. They’re hiding the context. That’s not misleading - it’s deliberate. A 2021 study found 78% of direct-to-consumer drug ads in the U.S. used relative risk without ever mentioning the absolute numbers.

Why Both Numbers Matter

You can’t understand a drug’s true impact by looking at just one number. Absolute risk tells you how likely you are to be affected. Relative risk tells you how much the drug changes that likelihood. Together, they give you the full picture.Take a common antidepressant like venlafaxine. Studies show 20% of people on this drug report sexual side effects, compared to 8.3% on a placebo. The relative risk is 2.41 - meaning you’re 2.4 times more likely to have this side effect. That sounds scary. But the absolute difference? Just 11.7 percentage points. So if you’re one of 100 people taking it, about 12 might have this issue. That’s not rare. But it’s not inevitable either. Knowing both numbers helps you weigh the trade-off: Will the mood improvement be worth the risk of sexual dysfunction?

Another example: Statins. A 2022 Reddit thread had a patient refuse the drug because he read it "cuts heart attack risk in half." His doctor explained his baseline risk was 2%. After statins, it dropped to 1%. The patient was shocked. "I thought it meant I’d have a 50% chance of avoiding a heart attack," he said. He didn’t realize that 98% of people like him won’t have a heart attack anyway - with or without the drug. The statin only helped 1 in 100. That’s useful for someone with a history of heart disease. Less so for a healthy 40-year-old with normal cholesterol.

How to Spot the Trick

Here’s how to tell when you’re being shown only half the story:- If you see a percentage like "50% reduction," ask: "Reduction from what?"

- If the ad says "lowers risk of stroke by 30%" but doesn’t say the starting risk, assume it’s tiny.

- Look for phrases like "compared to placebo" or "relative to untreated patients." If they’re missing, the number is probably relative.

- Check the small print. Many ads bury the absolute numbers in fine print or on a website link.

Drug companies aren’t lying. They’re just using a language most people don’t understand. The FDA doesn’t require absolute risk numbers in ads - only in the official prescribing information. That’s why you need to ask for it.

What Experts Say - And What You Should Do

Dr. Steve Woloshin and Dr. Lisa Schwartz from Dartmouth Institute say: "Always start with absolute risk. Then add relative risk for context." They recommend asking your doctor two questions:- "What’s my chance of having this problem without the drug?"

- "How much does the drug reduce that risk?"

They also suggest asking for visual tools - like a chart showing 100 people, with dots marking who gets helped and who gets side effects. One 2016 Cochrane Review found these pictograms improve patient understanding by 50%. A 2022 Harvard Medical School study showed that after a 30-minute training session, 68% of students could correctly interpret risk numbers - up from 32% before.

Regulations are slowly catching up. The FDA issued draft guidance in January 2023 asking drugmakers to show both absolute and relative risks in ads. The European Medicines Agency already requires both in patient leaflets. But enforcement is weak. Until that changes, you’re your own best defense.

Real-World Impact: When Numbers Change Decisions

One patient, Mrs. Smith, was told her blood pressure drug reduced her risk of stroke by 40%. She was ready to quit - until her doctor showed her the numbers. Her baseline risk was 5%. The drug lowered it to 3%. That’s a 2 percentage point drop. The 40% sounded big, but the real benefit was small. She asked, "Will I feel better?" The doctor said no - the drug doesn’t improve symptoms. She decided to skip it.Another patient, a 58-year-old with type 2 diabetes, was told his cholesterol drug cut his heart attack risk by 30%. His doctor showed him: without the drug, his 10-year risk was 20%. With it, it dropped to 14%. That’s a 6 percentage point improvement. He asked, "How many people like me need to take this to prevent one heart attack?" The answer: about 17. He said, "That’s worth it for me." He started the drug and stayed on it for five years.

That’s the difference. One person walked away because they thought the benefit was huge. The other stayed because they knew the truth.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need to be a statistician to understand drug risks. Here’s your simple checklist:- Ask your doctor for the absolute risk of the condition you’re treating.

- Ask for the absolute risk reduction from the drug.

- Ask for the Number Needed to Treat (NNT) - how many people need to take it for one to benefit?

- Ask for the absolute risk of side effects - not just "common" or "rare."

- Ask: "If I don’t take this, what’s my chance of getting worse?"

If your doctor doesn’t know the numbers, ask for the prescribing information. It’s online. Or ask for a patient leaflet from the manufacturer. Look for the section called "Clinical Studies" or "Adverse Reactions." That’s where the real numbers live.

Remember: A drug that cuts your risk by 50% might not help you at all - if your risk was tiny to begin with. And a drug that only lowers risk by 2% might save your life - if your risk was high.

Numbers don’t lie. But they can be dressed up to sound like they do. You just need to know how to read them.

What’s the difference between absolute risk and relative risk?

Absolute risk is your actual chance of experiencing a side effect or benefit - like a 1 in 100 chance of getting a headache. Relative risk compares your risk on the drug to someone not on it - like saying the drug cuts your risk in half. Absolute risk tells you what will happen to you. Relative risk tells you how much better or worse the drug makes it compared to nothing.

Why do drug ads always use relative risk?

Because relative risk numbers are bigger and sound more impressive. A drug that lowers heart attack risk from 2% to 1% has a 50% relative risk reduction - which sounds like a miracle. But the absolute improvement is just 1 percentage point. Ads use relative risk to make small benefits look big. It’s not illegal - it’s just misleading without context.

How do I know if a drug is worth taking?

Ask for your personal absolute risk - both for the condition and for side effects. Then ask for the absolute risk reduction the drug offers. If the benefit is small (like a 1-2% drop) and the side effects are common, it might not be worth it. If your baseline risk is high and the drug cuts it in half, the benefit is real. Always ask for the Number Needed to Treat (NNT) - it tells you how many people need to take the drug for one to benefit.

Can a drug have a high relative risk reduction but still be useless?

Yes. If your baseline risk is very low, even a 90% relative risk reduction might mean almost nothing. For example, if your chance of a rare side effect is 0.01% and the drug cuts it to 0.001%, that’s a 90% drop - but you’re still looking at 1 in 100,000. That’s not a meaningful benefit for most people. The real question is: Does this drug change my life - or just my statistics?

What should I ask my doctor about drug risks?

Ask: "What’s my chance of having this problem without the drug?" Then: "How much does the drug reduce that risk in real terms?" And: "How many people need to take this for one person to benefit?" Also ask: "What’s the absolute risk of the most common side effect?" Don’t accept answers like "common" or "rare." Ask for numbers.

So let me get this straight some pharma bro is gonna tell me i cut my heart attack risk in half but i was only at 2% to begin with so now im at 1% and they want me to take a pill every day for the rest of my life because of that

bro i dont even take tylenol unless my head is gonna explode