Every year, millions of unused or expired medications end up in bathrooms, kitchen drawers, or worse - flushed down the toilet. But here’s the truth: medication storage and disposal aren’t just about cleaning out your cabinet. They’re about keeping your family safe, protecting the environment, and following the law.

In New Zealand, like in many countries, improper handling of prescriptions contributes to accidental poisonings, drug abuse, and water contamination. The good news? You don’t need a degree in pharmacology to get it right. Just a few simple steps can make all the difference.

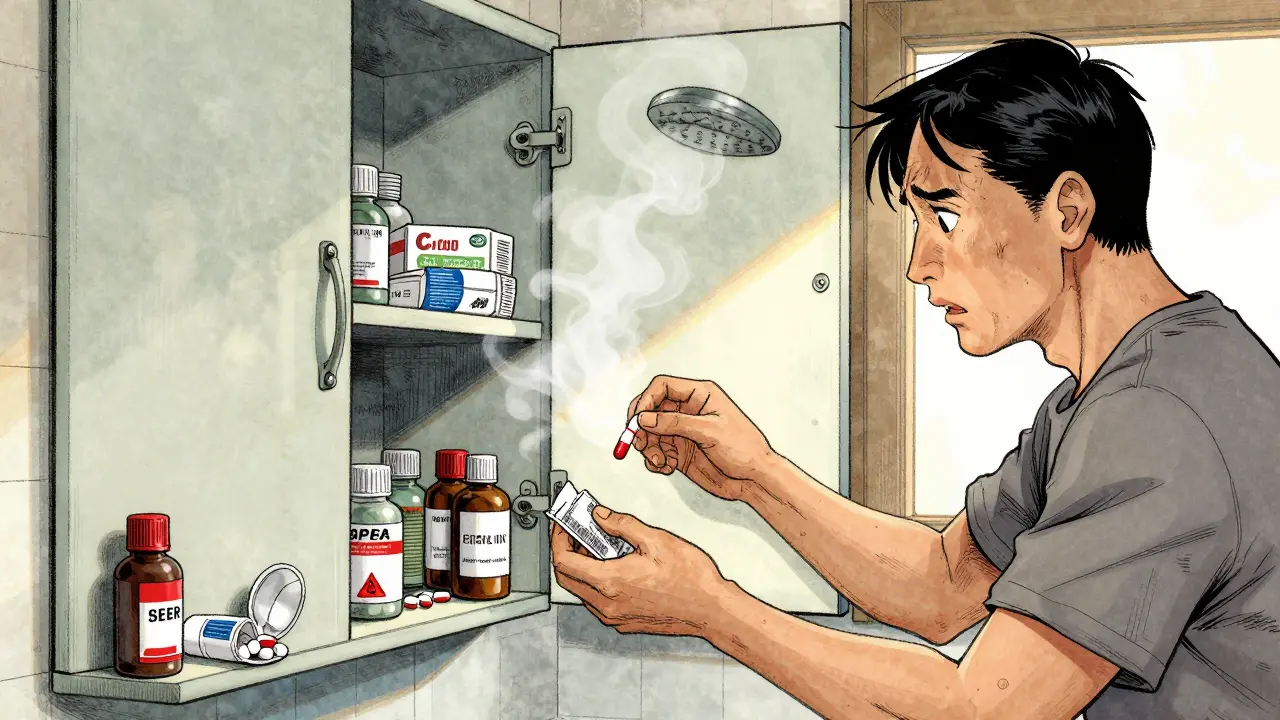

Where to Store Medications - And Where Not To

Your bathroom cabinet might seem like the obvious spot - it’s close to the sink, easy to reach, and you use meds there anyway. But heat and moisture from showers and sinks can break down pills and liquids, making them less effective or even dangerous. The same goes for storing medicines near the stove, in a hot car, or in direct sunlight.

The best place? A cool, dry spot out of reach of kids and pets. A locked cabinet in a bedroom or hallway works perfectly. If you have controlled substances like opioids, benzodiazepines, or stimulants, lock them up. Seriously. The DEA and health agencies agree: lock-box storage isn’t optional for these drugs. It’s the only way to prevent theft, accidental overdose, or misuse by teens or visitors.

Some medications need refrigeration - insulin, certain antibiotics, and biologics. Check the label. If it says “store between 2°C and 8°C,” keep it in the fridge, but not in the door where temperatures swing. Use a sealed container so it doesn’t absorb food odors.

Always keep medications in their original containers. That’s not just for looks - it has the name, dosage, expiration date, and prescribing doctor. If you transfer pills to a pill organizer, keep the original bottle nearby. You’ll need it if there’s an emergency or if you’re visiting a doctor.

What Happens When Medications Expire?

Expiration dates aren’t arbitrary. They’re based on testing to show when the drug will still work safely and effectively. After that date, potency drops. Some medications, like antibiotics, can become toxic. Others, like nitroglycerin for heart conditions, can fail when you need them most.

Don’t assume a pill is fine because it “looks okay.” Pills don’t mold like bread. They just lose strength. Liquid antibiotics, eye drops, and insulin are especially sensitive. If it’s been more than a year past the date - or if it’s changed color, smells odd, or looks cloudy - don’t risk it.

Here’s a quick rule: If you’re not sure, dispose of it. Better safe than sorry.

How to Dispose of Medications - The Right Way

The safest, most responsible way to get rid of unused meds? Use a take-back program. These are drop-off locations - often at pharmacies, hospitals, or police stations - where you can hand over old prescriptions without questions. In New Zealand, many pharmacies participate in national take-back initiatives. Check with your local pharmacy or visit the Ministry of Health website to find the nearest site.

But what if there’s no drop-off nearby? Or it’s after hours? Then you dispose of them at home - the FDA-approved way.

Here’s how:

- Remove pills or liquids from their original bottles.

- Mix them with something unappetizing - used coffee grounds, cat litter, or dirt. Don’t crush pills unless instructed. Just mix them in.

- Put the mixture in a sealed plastic bag or container. A used yogurt tub or old jar works.

- Scratch out or black out your name and prescription number on the empty bottle.

- Toss the sealed container in your household trash.

This method prevents pets or kids from finding pills, and keeps drugs out of the water system. Studies show it reduces environmental contamination by 99.8% compared to flushing.

What Should You Flush? (Spoiler: Almost Nothing)

You’ve probably heard you should flush certain meds. That used to be true - but it’s changed.

The FDA maintains a short list of drugs that are dangerous enough to flush only if no take-back option is available. As of 2023, that list includes 15 opioid painkillers like oxycodone and fentanyl patches, and one benzodiazepine: alprazolam (Xanax). These drugs can be deadly in small doses, especially to children. If you’re holding onto one of these and can’t get to a drop-off, flushing is the lesser of two evils.

For everything else - antibiotics, blood pressure pills, antidepressants, vitamins - don’t flush. Ever. Even if the bottle says “flush.” That’s outdated advice. Today’s rules say: trash it, don’t flush it.

Controlled Substances Are Different

Controlled substances - opioids, ADHD meds, sedatives - are tightly regulated. You can’t just drop them off at a pharmacy like a bottle of aspirin. In New Zealand, pharmacies can accept them for disposal, but only if they’re registered as authorized collectors. Most aren’t.

If you have unused controlled substances, call your local pharmacy first. Ask if they’re part of the national take-back program. If not, contact your district health board or local police station. Some have secure drop boxes for these drugs.

Never give them to friends, sell them, or toss them in the trash without mixing them first. Even one pill can be fatal to someone else.

Why This Matters - Beyond Your Home

Every year, an estimated 247 million pounds of pharmaceuticals enter U.S. waterways. That’s not just from flushing - it’s from landfills leaching into groundwater, from improper hospital disposal, and from people throwing pills in the trash without sealing them.

These chemicals show up in rivers, lakes, and even drinking water. Fish have shown signs of hormonal disruption. Microplastics from pill coatings are now found in human blood. It’s not science fiction - it’s science fact.

Proper disposal isn’t just personal hygiene. It’s environmental responsibility. And it’s the law.

What Healthcare Facilities Do Differently

Hospitals, nursing homes, and clinics have strict rules. They can’t just throw meds in the trash. Hazardous pharmaceutical waste - about 5-10% of all meds - must be incinerated at licensed facilities. That includes chemo drugs, certain antibiotics, and anything on the EPA’s P-list or U-list.

They use special, labeled, leak-proof containers. Staff get trained every year. Records of destruction must be kept for three years. And flushing? Completely banned since 2019 under EPA Subpart P.

It’s expensive - facilities spend an average of $12,500 extra per year just to comply. But it’s necessary. And it’s why you shouldn’t assume what’s okay at home is okay at work.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

- Mistake: Keeping old meds “just in case.” Fix: Clean out your cabinet every six months. If you haven’t used it, you probably won’t.

- Mistake: Sharing prescriptions. Fix: Never give your meds to anyone else. Even if they have the same symptoms. Dosing is personal.

- Mistake: Using the sink for disposal. Fix: Unless it’s on the FDA flush list, don’t. Trash is safer.

- Mistake: Thinking expiration dates are just a suggestion. Fix: Treat them like a fire alarm - if it goes off, act.

What You Can Do Today

Here’s a simple action plan:

- Go to your medicine cabinet right now. Pull out everything you haven’t used in the last year.

- Check expiration dates. Toss anything expired or changed.

- Separate controlled substances (opioids, sedatives, stimulants).

- Call your pharmacy. Ask if they take back meds. If yes, drop them off.

- If no take-back is available, mix the rest with coffee grounds or cat litter. Seal it. Toss it.

- Scratch out your info on empty bottles. Recycle them if your council allows it.

That’s it. Five minutes. One cabinet. One less risk in your home.

Medication safety isn’t about perfection. It’s about progress. Start small. Do one thing right. And keep going.

Can I flush my old pills down the toilet?

Only if they’re on the FDA’s flush list - which includes 15 opioid painkillers and one benzodiazepine (alprazolam). For every other medication, flushing is harmful and prohibited. The safest method is to mix pills with coffee grounds or cat litter, seal them in a container, and throw them in the trash.

Where can I find a drug take-back location near me?

In New Zealand, many pharmacies, hospitals, and police stations participate in national take-back programs. Check the Ministry of Health website or call your local pharmacy. You can also ask at your GP’s office - they often have information on nearby drop-off points. Take-back is the most environmentally safe option.

Do I need to crush my pills before disposing of them?

No, crushing is not required and can be dangerous with certain medications like extended-release pills. Instead, remove them from the bottle and mix them with something unappealing - like used coffee grounds, cat litter, or dirt. This makes them unattractive to kids or pets and prevents extraction.

What should I do with empty medicine bottles?

Scratch out or cover your name, prescription number, and any personal info with a permanent marker. Then remove the label if possible. Most councils accept empty plastic bottles in recycling - check your local rules. If unsure, throw them in the trash.

Is it safe to store medications in the fridge?

Only if the label says so. Insulin, some antibiotics, and biologics need refrigeration between 2°C and 8°C. Store them in a sealed container to avoid absorbing food smells. Never store them in the fridge door - temperature changes there can damage them. Most other meds should stay at room temperature, away from humidity.

Why can’t I just throw my old pills in the trash without mixing them?

Unmixed pills in the trash can be found by children, pets, or people going through the garbage. Mixing them with coffee grounds or cat litter makes them unappealing and hard to extract. It also prevents the drugs from leaching into soil and groundwater over time. This simple step protects both people and the environment.

What happens if I accidentally flush a medication that shouldn’t be flushed?

One accidental flush won’t cause immediate harm, but repeated flushing contributes to long-term water contamination. Pharmaceuticals in waterways affect aquatic life and can enter the human food chain. If you’ve done this before, don’t panic - just switch to the correct method going forward. Use take-back programs or the coffee grounds method for all future disposal.

What Comes Next

Medication safety is evolving. More pharmacies are installing secure drop boxes. New Zealand is expanding its take-back network. And by 2025, manufacturers may be required to fund disposal programs - shifting the burden from consumers to producers.

But right now, you hold the power. You can stop the cycle of waste, misuse, and pollution - one cabinet cleanup at a time.

Don’t wait for a law to change. Don’t wait for someone else to act. Do it today. Your family, your community, and your planet will thank you.

So many people don’t realize how dangerous old meds can be-especially with kids around. I cleaned out my cabinet last month and found three expired antibiotics and my ex’s Xanax. Yikes. I mixed everything with coffee grounds and tossed it. Feels good to do the right thing, even if it’s small.