Every time you pick up a prescription bottle with a generic label instead of the brand name, you’re seeing the result of something called an ANDA. It’s not a drug. It’s not a company. It’s a paperwork process - but one that saves Americans billions every year and keeps medicines affordable. If you’ve ever wondered how a $200 brand-name pill becomes a $5 generic, the answer starts with the Abbreviated New Drug Application.

What exactly is an ANDA?

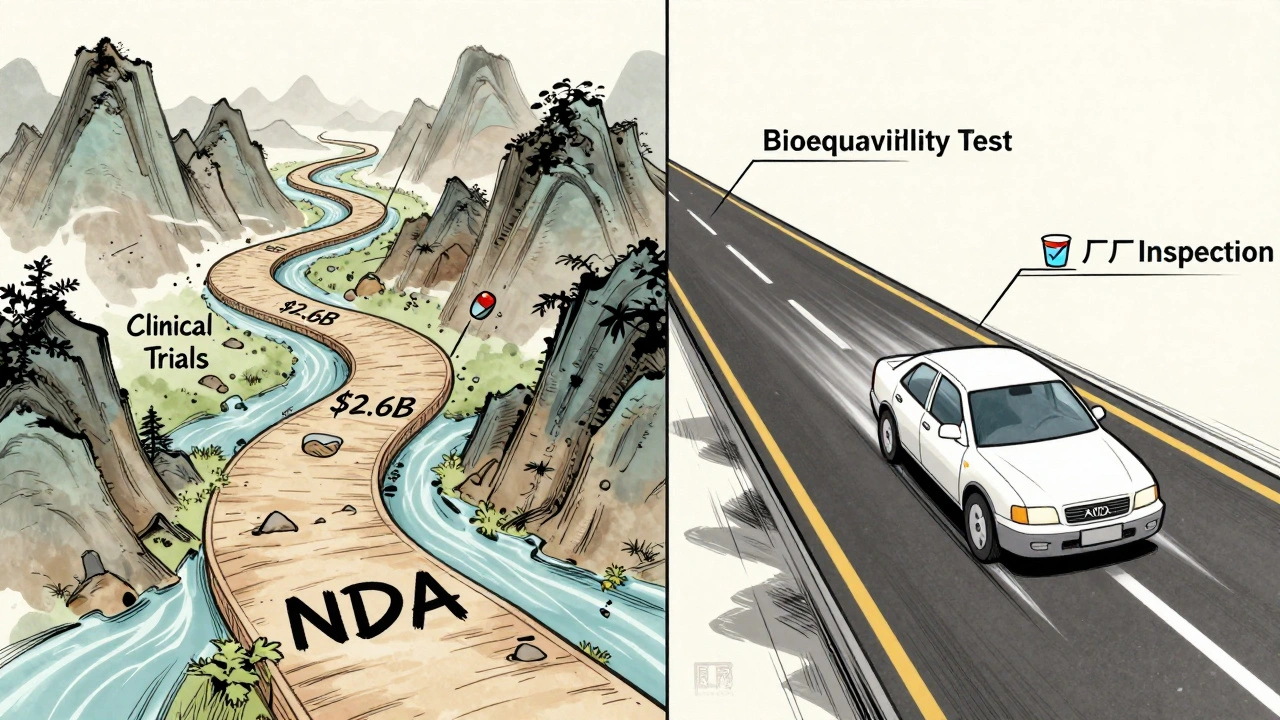

An ANDA, or Abbreviated New Drug Application, is the official form a company submits to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to get approval to sell a generic version of a brand-name drug. The word "abbreviated" is key here. Unlike the original drug maker, who had to run full clinical trials to prove their drug was safe and effective, a generic company doesn’t need to start from scratch. They just need to prove their version works the same way.

The FDA doesn’t require them to repeat animal studies or human trials. Instead, they rely on the data already approved for the original drug - called the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). This saves time, money, and lives. Since the Hatch-Waxman Act passed in 1984, over 11,000 generic drugs have been approved through the ANDA pathway. Today, nine out of every ten prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generics.

How does an ANDA prove a generic drug works the same?

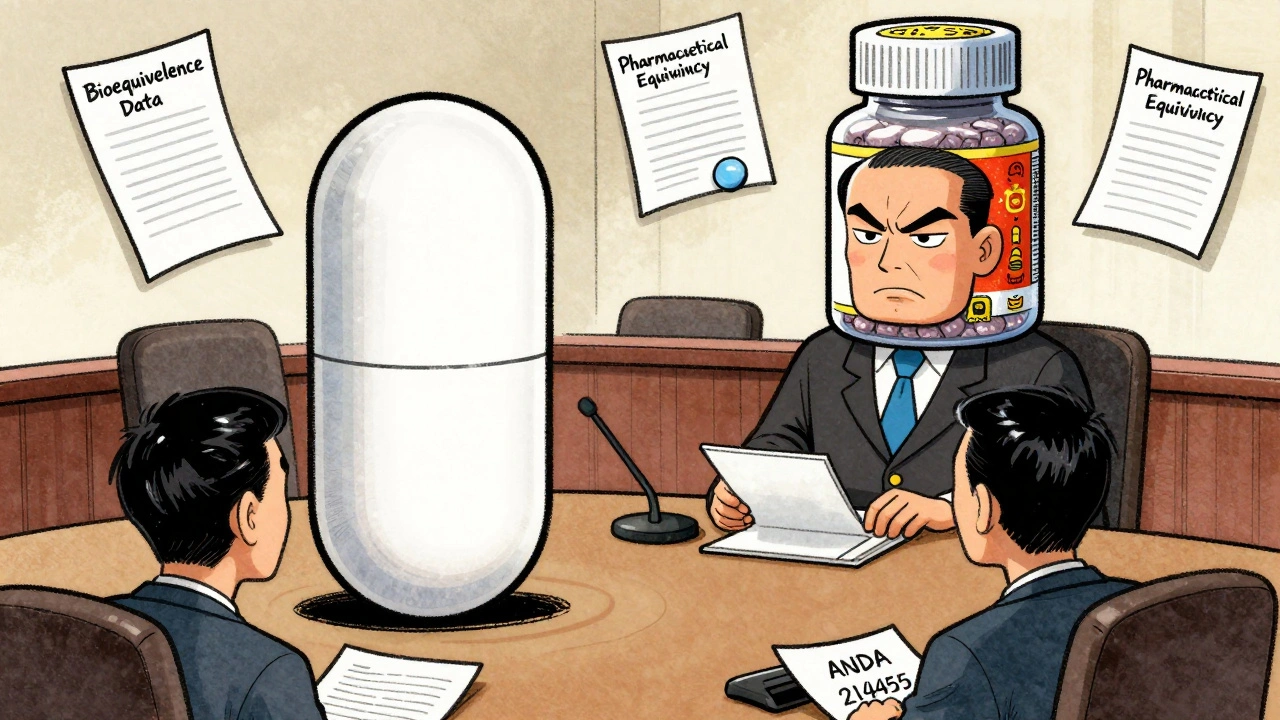

It’s not enough for a generic pill to look like the brand name. It needs to act like it. That’s where two critical tests come in: pharmaceutical equivalence and bioequivalence.

Pharmaceutical equivalence means the generic has the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form (tablet, capsule, injection), and route of administration (oral, topical, etc.) as the brand. If the brand is a 10mg tablet taken by mouth, the generic must be identical in those ways.

Bioequivalence is the real test. It’s done with 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. Researchers give them the brand drug and the generic, then measure how much of the drug enters the bloodstream and how fast. The results must show that the generic delivers the same amount of medicine at the same rate - within a very tight range. Specifically, the 90% confidence interval for both the total exposure (AUC) and peak concentration (Cmax) must fall between 80% and 125% of the brand drug’s numbers. If it’s outside that range, the FDA says it’s not equivalent.

This isn’t theoretical. In 2023, the FDA reported a 97% therapeutic equivalence rate between generics and brand-name drugs. That means for nearly every single case, patients get the same clinical results - whether they take the brand or the generic.

What’s the difference between an ANDA and an NDA?

Every new drug starts with a New Drug Application, or NDA. This is the full-blown, multi-year, billion-dollar process. The original manufacturer must prove safety and effectiveness through years of lab work, animal testing, and multiple phases of human clinical trials. The average NDA takes 10 to 15 years and costs around $2.6 billion to bring to market.

An ANDA? It’s the shortcut. No new clinical trials. No new safety data. Just proof that the generic matches the brand in every meaningful way. The average ANDA takes 3 to 4 years and costs between $1 million and $5 million. That’s a massive difference.

And the FDA reviews them faster, too. Under the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), standard ANDAs are reviewed in 10 months. Compare that to a standard NDA, which can take up to 12 months - and that’s without the extra time for clinical trials.

What can’t an ANDA be used for?

Not every drug can go generic this way. The ANDA pathway works best for simple, small-molecule drugs - the kind you swallow or inject. It struggles with complex products.

Think inhalers, topical creams, nasal sprays, or drugs with very narrow therapeutic windows - where even tiny differences in absorption can cause serious side effects. For these, proving bioequivalence isn’t as straightforward. The FDA has started special programs to handle them, but approval is harder and slower. In 2022, 68% of generic manufacturers reported major challenges submitting ANDAs for these complex products.

Also, you can’t file an ANDA until the brand-name drug’s patents and exclusivity periods expire. That’s why you don’t see generics for brand-new drugs. The patent clock has to run out first. And when someone does file an ANDA before patent expiry, they have to certify that the patent is invalid or won’t be infringed - which often triggers lawsuits and delays approval by up to 30 months.

Who benefits from ANDAs?

Everyone does - but the biggest winners are patients and the healthcare system.

Generic drugs save the U.S. healthcare system over $300 billion every year. In 2022 alone, 724 new generic approvals were expected to save $23.7 billion. Prices for generics typically drop 80% to 85% within a year of launch. A drug that costs $500 a month as a brand can become $50 as a generic - sometimes even less.

And it’s not just about cost. It’s about access. Millions of people can’t afford brand-name drugs. Without ANDAs, many wouldn’t take their medications at all. The FDA estimates that generic drugs account for 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. - and only 23% of total drug spending. That’s the power of competition.

What goes into an ANDA submission?

It’s not just a form. It’s a massive technical package. A complete ANDA includes:

- Proof of pharmaceutical equivalence

- Bioequivalence study results

- Detailed manufacturing process descriptions

- Quality control methods for every batch

- Stability data showing the drug won’t break down over time

- Labeling that matches the brand, except for the company name and logo

Manufacturers also have to prove their factory meets FDA standards. Inspections happen before approval - and randomly after. If the FDA finds issues, they send a "complete response letter" - basically a rejection with a list of fixes needed. The most common reasons? Inadequate manufacturing controls (32% of cases) and weak bioequivalence data (27%).

Since 2017, all ANDAs must be submitted electronically using the eCTD format. This cut administrative errors by 60%. Still, it takes most companies 18 to 24 months just to learn how to do it right.

Who’s behind the ANDA system?

The ANDA pathway was created by the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. It was a compromise: give brand-name companies extra patent protection to reward innovation, but let generics enter quickly after patents expire to drive down prices. It worked. Since then, the generic drug market has grown at 4.2% annually.

Today, the top generic manufacturers - Teva, Viatris, and Sandoz - control nearly half the U.S. market. But thousands of smaller companies also file ANDAs. The FDA assigns each approved ANDA a unique six-digit number - like ANDA 214,455 for the generic version of Eliquis. That number is the official record that the drug is approved and safe to sell.

What’s changing in the ANDA world?

The FDA isn’t resting. Under GDUFA IV (2023), they’re aiming for 90% of ANDAs to get approved on the first try by 2027. Right now, it’s around 65%. They’re also expanding the program to cover more complex drugs - like inhalers and topical treatments - which used to be nearly impossible to get approved as generics.

But there’s a risk. Over 80% of the active ingredients in U.S. generics come from just two countries: India and China. If a factory in one of those countries gets shut down for quality issues - as happened with a major supplier in 2020 - it can cause nationwide shortages. Experts warn that this over-reliance creates systemic risk.

Still, the future of ANDAs looks strong. The Congressional Budget Office projects that between 2024 and 2033, generic drugs will save the U.S. healthcare system $1.7 trillion. That’s not just a number. It’s millions of people getting the medicine they need without having to choose between rent and refills.

Why does this matter to you?

If you or someone you know takes medication regularly, the ANDA system is working for you. It’s why your co-pay is lower. Why you don’t have to skip doses. Why you can afford to stay on your treatment.

It’s not glamorous. No one’s making ads for ANDAs. But behind every generic bottle, there’s a team of scientists, regulators, and manufacturers who made sure it was safe, effective, and affordable. That’s the real story.

Is an ANDA the same as a generic drug?

No. An ANDA is the application a company submits to the FDA to get approval to make a generic drug. The generic drug is the actual product you get at the pharmacy. The ANDA is the paperwork that makes it legal to sell.

Can a generic drug be different from the brand name?

Yes - but only in ways that don’t affect how it works. Generics can have different colors, shapes, or inactive ingredients (like fillers or dyes). The active ingredient must be identical. Packaging and labeling can differ too - but the dosage instructions and warnings must match the brand.

How long does it take to get an ANDA approved?

Under current FDA rules, a standard ANDA takes about 10 months to review. But preparation takes years - often 3 to 4 years - before the application is even submitted. Delays can happen if the FDA requests more data or if patent disputes arise.

Are generic drugs as safe as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generics to meet the same strict standards for quality, strength, purity, and stability as brand-name drugs. Over 97% of generic drugs approved through ANDAs have been shown to work the same as their brand-name counterparts in real-world use.

Why are generic drugs cheaper?

Because generic companies don’t have to repeat expensive clinical trials. They also face competition - multiple companies can make the same generic once patents expire. That drives prices down. Brand-name companies recover R&D costs through high prices; generics compete on cost.

Let me tell you something-this ANDA system is the only reason I can afford my blood pressure meds. I used to skip doses because the brand cost $400 a month. Now? $12. The FDA didn’t do this for fun. Someone fought for this. And now people like me don’t have to choose between insulin and groceries.

Stop acting like generics are ‘inferior.’ I’ve been on them for 7 years. My labs haven’t changed. My doctor can’t tell the difference. The science is solid.